Detached and Torn Retina

A retinal detachment is a very serious problem that almost always causes blindness unless treated. The appearance of flashing lights, floating objects, or a gray curtain moving across the field of vision are all indications of a retinal detachment. If any of these occur, see an ophthalmologist right away.

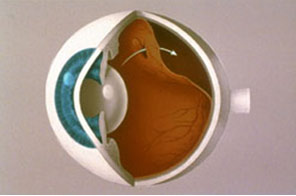

As one gets older, the vitreous, the clear gel-like substance that fills the inside of the eye, tends to shrink slightly and take on a more watery consistency. Sometimes as the vitreous shrinks it exerts enough force on the retina to make it tear.

Retinal tears increase the chance of developing a retinal detachment. Fluid vitreous, passing through the tear, lifts the retina off the back of the eye like wallpaper peeling off a wall. Laser surgery or cryotherapy (freezing) are often used to seal retinal tears and prevent detachment.

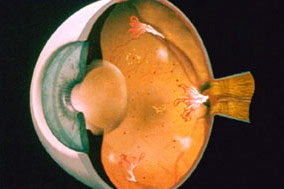

|

| A retinal detachment begins as a small hole in the retina. As fluid collects behind the retina, more of it is detached. |

If the retina is detached, it must be reattached before sealing the retinal tear. There are three ways to repair retinal detachments. Pneumatic retinopexy involves injecting a gas bubble into the eye that pushes on the retina to seal the tear. The scleral buckle procedure requires the fluid to be drained from under the retina before a flexible piece of silicone is sewn on the outer eye wall to give support to the tear while it heals. Vitrectomy surgery removes the vitreous gel from the eye, replacing it with a gas bubble, which is slowly replaced by the body’s fluids.

Age-Related Macular Degeneration (AMD)

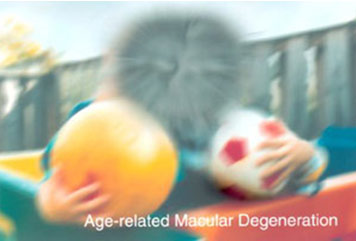

Macular degeneration is the most common cause of legal blindness in developed countries and affects up to 1 in 10 patients over the age of 60 in the United States. Macular degeneration affects the central portion of the retina, the layer of tissue which detects light and lines the inner surface of the eye (similar to film in a camera). As the disease progresses, the central portion of the retina is damaged and results in a decrease in the central vision (see simulated photo below).

|

| Simulation of the distorted central vision of a patient with macular degeneration. |

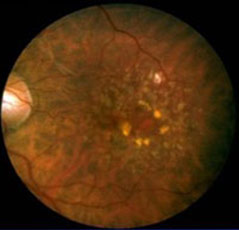

Damage to the retina can be seen by your eye doctor in the form of yellowish deposits in the retina (drusen) in the early form of the disease and by atrophy (or cell death) as the macular degeneration progresses.

|

| Picture of the retina of a patient with macular degeneration. Notice the yellowish deposits (drusen) in the center of the picture. |

About 10% of patients develop blood vessel growth (neovascularization) underneath the retina, which can lead to a precipitous drop in vision. This is called the “wet” form of AMD. In some of these patients, the use of a laser to destroy the abnormal blood vessels can help stabilize the vision. In other cases, injection of medications such as Avastin, Lucentis, or Eylea may stabilize or even reverse some of the effects of AMD. The vast majority of patients with macular degeneration have the “dry” form of AMD, in which the progression of disease is slow and is related to a gradual cellular death in the central retina (atrophy). Until recently, there was no scientifically proven treatment for these patients. However, a recent study (the Age-Related Eye Disease Study, or AREDS) funded by the National Eye Institute revealed that daily supplementation with vitamins A, C, E, and zinc delayed the progression of macular degeneration. Specifically, almost 4000 patients with mild, intermediate, or advanced AMD were enrolled in the study and followed for an average of more than 6 years. Patients were randomly assigned to receive daily oral tablets containing 1) high doses of antioxidants (vitamins A, C, and E); 2) zinc; 3) antioxidants plus zinc; or 4) placebo. In patients with intermediate or advanced forms of macular degeneration, supplementation with antioxidants plus zinc decreased their risk for advancement by 25% over the follow-up period! More details of the results of this study can be seen here.

Based on this study, Caplan Eye Clinic recommends that all patients with intermediate or advanced forms of macular degeneration take oral vitamin and zinc supplementation at the dosages used in the study.

A variety of brands are available over-the-counter at most drugstores. Be sure that they contain the following vitamins and zinc in the dosages indicated: vitamin C, 500 mg; vitamin E, 400 IU; beta carotene, 15mg; zinc, 80 mg, as zinc oxide; and copper, 2 mg, as cupric oxide. Smokers should be careful taking high dosages of vitamin A, as some studies have shown this to increase mortality rates.

You can monitor your central vision for the progression of macular degeneration using an Amsler grid (see below). A rapid change in the central distortion of your vision may indicate the “wet” form of macular degeneration (see above) which may be amenable to laser treatment. The Amsler grid test consists of a grid of lines. The grid should be held about 12 inches from the eyes and each eye should be tested independently. While looking at the central dot with each eye separately, be sure that you can see all four corners of the grid. If not, or if any of the lines are blurry, wavy, distorted, bent, gray, or missing, you should call Caplan Eye Clinic to have your eyes examined. We recommend using the grid at least once a week. You can remind yourself of this by placing the grid in a convenient place (i.e. on the refrigerator door or bathroom mirror). Use the grid below to take the test on your computer screen.

|

Diabetic Retinopathy

NONPROLIFERATIVE DIABETIC RETINOPATHY (NPDR)

If you have diabetes mellitus, your body does not use and store sugar properly. Over time, diabetes can damage blood vessels in the retina, the nerve layer at the back of the eye that senses light and helps to send images to the brain. The damage to retinal vessels is referred to as diabetic retinopathy.

Nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy (NPDR), commonly known as background retinopathy, is an early stage of diabetic retinopathy. In this stage, tiny blood vessels within the retina leak blood or fluid. The leaking fluid causes the retina to swell or to form deposits called exudates.

|

| NPDR is seen in the retina as tiny hemorrhages and areas of leaking fluid. |

Many people with diabetes have mild NPDR, which usually does not affect their vision. When vision is affected, it is the result of macular edema and/or macular ischemia.

Macular edema is swelling, or thickening, of the macula, a small area in the center of the retina that allows us to see fine details clearly. The swelling is caused by fluid leaking from retinal blood vessels. It is the most common cause of visual loss in diabetes. Vision loss may be mild to severe, but even in the worst cases, peripheral (side) vision continues to function. Laser treatment can be used to help control vision loss from macular edema.

|

| Defects in vision resulting from chronic macular edema in a diabetic. |

Macular ischemia occurs when small blood vessels (capillaries) close. Vision blurs because the macula no longer receives sufficient blood supply to work properly. Unfortunately, there are no effective treatments for macular ischemia.

A medical eye examination is the only way to find changes inside your eye. If your ophthalmologist finds diabetic retinopathy, he or she may order color photographs of the retina or a special test called fluorescein angiography to find out if you need treatment. In this test a dye is injected in your arm and photos of your eye are taken to detect where fluid is leaking.

If you have diabetes, early detection of diabetic retinopathy is the best protection against loss of vision. You can significantly lower your risk of vision loss by maintaining strict control of your blood sugar and visiting your ophthalmologist regularly. People with diabetes should schedule examinations at least once a year. Pregnant women with diabetes should schedule an appointment in the first trimester because retinopathy can progress quickly during pregnancy. More frequent medical eye examinations may be necessary after the diagnosis of diabetic retinopathy.

PROLIFERATIVE DIABETIC RETINOPATHY (PDR)

Proliferative diabetic retinopathy is a complication of diabetes caused by changes in the blood vessels of the eye. If you have diabetes, your body does not use and store sugar properly. High blood sugar levels create changes in the veins, arteries and capillaries that carry blood throughout the body. This includes the tiny blood vessels in the retina, the light-sensitive nerve layer that lines the back of the eye.

In PDR, the retinal blood vessels are so damaged they close off. In response, the retina grows new, fragile blood vessels. Unfortunately, these new blood vessels are abnormal and grow on the surface of the retina, so they do not resupply the retina with blood.

|

| PDR results in aggressive new blood vessel growth that, if left untreated, can lead to blindness. |

Occasionally, these new blood vessels leak and cause a vitreous hemorrhage. Blood in the vitreous, the clear gel-like substance that fills the inside of the eye, blocks light rays from reaching the retina. A small amount of blood will cause dark floaters, while a large hemorrhage might block all vision, leaving only light and dark perception.

The new blood vessels can also cause scar tissue to grow. The scar tissue shrinks, wrinkling and pulling on the retina and distorting vision. If the pulling is severe, the macula may detach from its normal position and cause vision loss.

Laser surgery may be used to shrink the abnormal blood vessels and reduce the risk of bleeding. The body will usually absorb blood from a vitreous hemorrhage, but that can take days, months or even years. If the vitreous hemorrhage does not clear within a reasonable time, or if a retinal detachment is detected, an operation called a vitrectomy can be performed. During a vitrectomy, the eye surgeon removes the hemorrhage and the abnormal blood vessels that caused the bleeding.

People with PDR sometimes have no symptoms until it is too late to treat them. The retina may be badly injured before there is any change in vision. There is considerable evidence to suggest that rigorous control of blood sugar decreases the chance of developing serious proliferative diabetic retinopathy.

Because PDR often has no symptoms, if you have any form of diabetes you should have your eyes examined.

Fluorescein Angiography

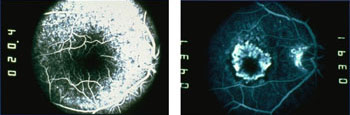

Fluorescein angiography, a clinical test to look at blood circulation inside the back of the eye, aids in the diagnosis of retinal conditions associated with diabetes, age-related macular degeneration, and other eye abnormalities. The test can also help follow the course of a disease and monitor its treatment. It may be repeated on multiple occasions with no harm to the eye or body.

Fluorescein, a harmless orange-red dye, is injected into a vein in the arm. The dye travels through the body to the blood vessels in the retina, the light-sensitive nerve layer at the back of the eye. A special camera with a green filter flashes a blue light into the eye and takes multiple photographs of the retina. The technique uses regular photographic film. No X-rays are involved.

If there are abnormal blood vessels, the dye leaks into the retina or stains the blood vessels. Damage to the lining of the retina or atypical new blood vessels may be revealed as well. These abnormalities are determined through a careful interpretation of the photographs by an ophthalmologist.

|

| A fluorescein angiogram reveals areas of leaking fluid from retinal blood vessels. |

The dye can discolor skin and urine until it is removed from the body by the kidneys. There is little risk in having fluorescein angiography, though some people may have mild allergic reactions to the dye. Severe allergic reactions have been reported but very rarely. Being allergic to X-ray dyes with iodine does not mean you’ll be allergic to fluorescein. Occasionally, some of the dye leaks out of the vein at the injection site, causing a slight burning sensation that usually goes away quickly.